In the aftermath of the deadliest bus crash in recent Hong Kong history, bus drivers continue to face low pay and long hours, with ever increasing pressure on their shoulders

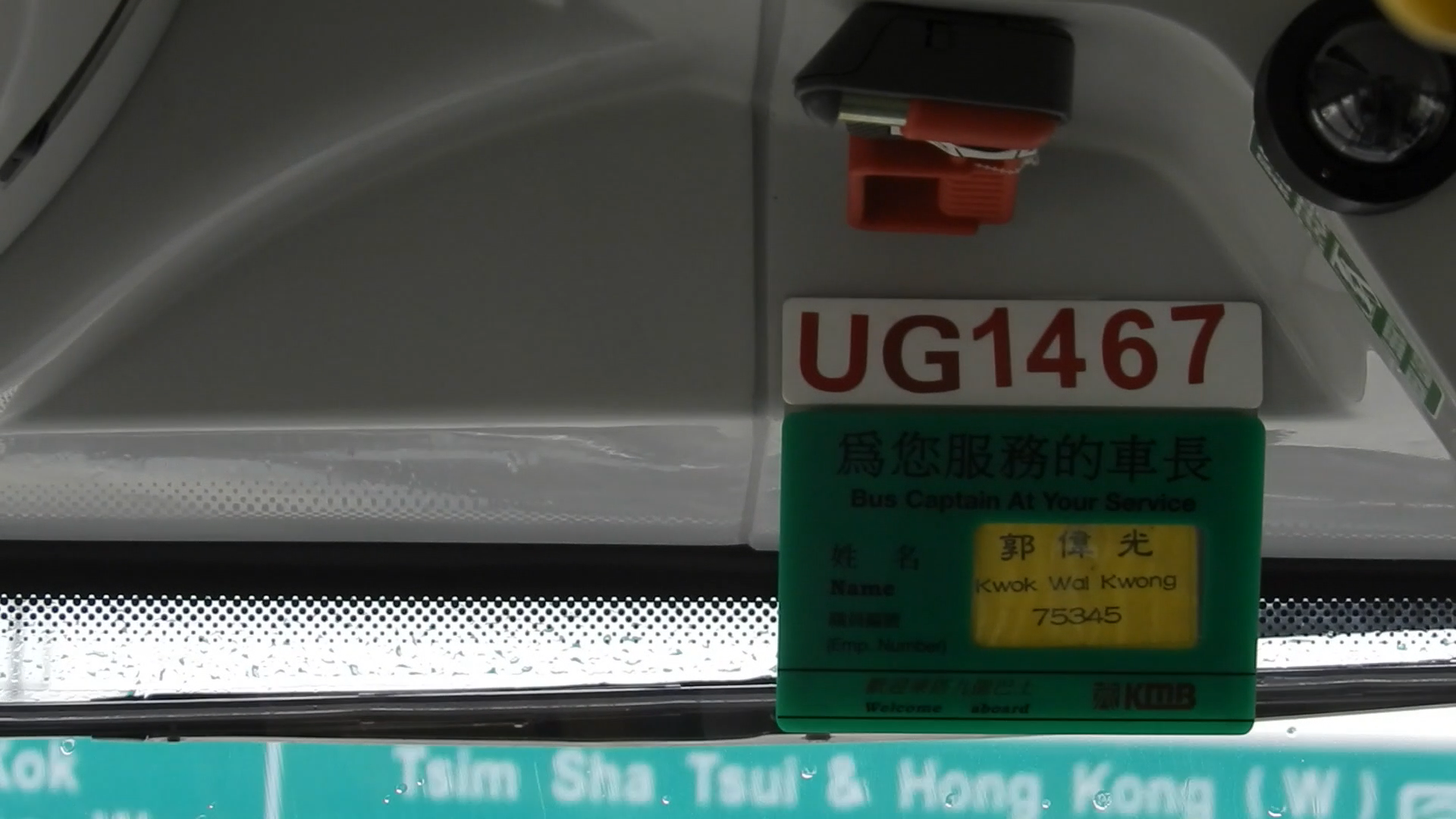

Kwok Wai-kwong, a KMB bus captain for 30 years, is already up at the break of dawn. He has a 14-hour shift ahead of him, but to get to work, he must leave his Tsing Yi home at 6am to begin his 45-minute commute to KMB’s bus depot on Stonecutters Island, where he will drive a route 935 double-decker to On Yam Estate, Kwai Chung, at half past seven. From there on, he will start ferrying passengers, back and forth, to Wan Chai on the other side of Hong Kong.

Kwok, who is turning 60 this year, has driven this route for almost 15 years.

But today is different. It is 13 March, just over a month after a horrific traffic accident in Tai Po took the lives of 19 people aboard a KMB bus and injured 66. It is also the day that the bus company rolls out new work schedules that purportedly comply with new Transports Department guidelines that aim to reduce bus drivers’ working hours.

The new guidelines, released in late February in the face of mounting public pressure, have shortened maximum duty hours from 14 to 12, and maximum driving hours from 11 to 10. But there is one caveat: it has formally introduced “special shifts” during morning and evening peak hours. Drivers on these duties would need to work up to 14 hours a day, although with a mandatory three-hour break in between.

That break, however, does not count as work time, meaning that drivers would only receive a $20 hourly subsidy.

Ironically, Kwok has been given a new special shift schedule that not only increases his daily driving hours from 9 to 11, but also cuts his rest time by half, to about two hours.

Kwok, who is also the vice president of KMB Staff Union, says three days ago, the company’s depot general manager Patrick Pang Shu-hung had a meeting with bus drivers. It proved to be fruitless nevertheless, as Kwok’s complaint about the grueling 14-hour special shift was met with a stonewall.

“If you don’t like it, don’t drive,” Pang reportedly said.

The Impossible hours

But Kwok has to drive on.

His first trip departs at 7:34am in Kwai Chung, and arrives at Wan Chai Terminus by 9am. From there he will have to head to the Cross-Harbour Tunnel to pick up passengers for Kennedy Town, immediately followed by another round trip to Shek Kip Mei by noon.

Five hours on the road, Kwok only had a sip of water. “I wouldn’t dare to drink more than a sip, sometimes you really don’t have time for toilet breaks,” he says. But he is lucky today, he feels, that he can spare a minute or two to use the restroom at Kennedy Town station. What seems like a basic human right is a rare privilege for bus drivers who are burdened by impossible schedules, despite the Transport Department’s guidelines stipulating a 12-minute rest break for the first four driving hours.

Under the old schedule, Kwok would have a four-hour lunch break in the afternoon, but that has been cut short by half under the new arrangement.

“No word can describe how exhausted I am by the last trip. Every part of my body hurts, sometimes my eyes will get watery,” he says.

After he finishes the final leg at 8pm from Mong Kok to Tsuen Wan, Kwok will still have to return the vehicle to the Stonecutters Island depot, which is at least another half an hour drive away. He is almost dead on his feet by the time he returns home for dinner at 9:30pm.

The routine repeats eight hours later in the next day.

Weeks after the introduction of the new schedules, the long hours have taken a toll on Kwok, who had a minor accident in late March at a station and scratched a bit of bodywork. It was a worrying sign for a long-serving and safety award-winning driver like him.

When special becomes norm

Kwok’s case is just the tip of the iceberg. A delve into other special-shift schedules reveals some 12-hour duties that entail 11 hours of continuously driving.

“The original intent of special shifts was to handle the morning and evening peak times. 20 years ago I only had to do two round trips in the morning and another round trip after the afternoon break. But then the company felt it was ‘wasteful’, so they started squeezing in as many trips as possible,” says Kwok.

“They would make drivers to drive to a terminus empty so you save the time on picking up and dropping off passengers or being stuck in traffic, and that in return increases the number of trips you do.

“Sometimes they make you cover for someone’s rest break, so it’s common you need to drive three different routes in a day,” he adds.

Special-shift drivers are also required to take their buses back to the depots during their midday breaks for tasks like inspecting and installing bus adverts, which all eat into their precious and much needed rest time.

Since the introduction of the new government guidelines on bus driving, some trade unions, including Kwok’s, have raised concerns that the provisions on special-shift duties would legitimise fatigue driving.

“Where are we supposed to go in that three-hour break? Some stations don’t have staff break rooms. Even if there are, they are usually small and crowded. Can drivers really rest? How do you prevent drivers from disregarding the risk of fatigue driving and taking on extra shifts for some overtime money?” he asks.

‘I am selling my blood”

When the new guidelines were introduced in February, a Transport Department spokesperson said: “The department had to strike a balance among the provision of proper bus services for the passengers, the rest times and working hours of bus captains, and the operational needs of the bus companies.”

It is certainly a precarious balance, because some drivers do fear that a reduction in working hours will affect their actual income.

According to Legislative Council documents, 10 to 20 per cent of KMB bus drivers worked special shifts in 2015, meaning there are more than a thousand drivers like Kwok who have to endure a 14-hour shift every day. As one driver says: “it’s like I’m selling my blood, exchanging time for money. I have no choice.”

KMB’s pay scale is complicated, with different salary calculation methods applying to drivers hired in different years. However, the situation for those employed after 2004 is particularly dire. At the peak of an economic crisis following the 2003 SARS outbreak, new drivers had their basic monthly salary reduced to $6,250 and their year-end bonus striped. The basic pay would only increase to about $10,000 after more than ten years of service, which is just on par with what new intakes in the past few years get. They could receive a maximum of $3,000 in annual bonuses, but they were discretionary in nature.

The company has recently made discretionary bonuses a part of drivers’ basic salary, which raises their monthly wage to $15,465, but that is still lower than the industry average of $17,089 as of the fourth quarter of 2017.

Struggling to make ends meet by relying on basic salaries, it is an open secret that, in exchange for more generous overtime pay, drivers would work longer hours or even take on extra shifts during break times, which violates industry rules. So for a special-shift driver employed in 2004, working 14 hours a day, 25 days a month, would increase his monthly income to about $23,000.

Kwok, employed under older and better pay scale in 1988, is sympathetic towards his less fortunate colleagues. “I was already earning $20,000 a month in 1998. But these drivers are earning even less than that after more than ten years into the job.”

In 2010, in protest of low and unequal pay, Kwok and his colleagues at the union slept on the streets for five days, forcing KMB to introduce a $6,000 “annual performance bonus” for new drivers who were not entitled to year-end double pay. But then its assessment criteria remains unclear, while pay gaps between drivers on different scales continue to divide them.

Deadly lessons

As early as 2004, the Legislative Council has passed a motion urging the government to cap bus drivers’ working and driving hours to ten and eight respectively. Lawmakers have also repeatedly questioned the safety risks of the 14-hour special shift.

The suggestions were ignored during the two revisions of official guidelines on bus driving in 2007 and 2010. Even after a bus crash in 2012, the department again rejected a Legco’s call to review the current industry guidelines.

According to government statistics, 16 per cent of some 16,000 traffic accidents happened in 2016 involved buses, which resulted in a total casualties of 3,500. But the government has continued to deny a link between drivers’ poor working conditions and high accident rates.

A demand by Kwok’s union to reduce maximum hours was also rejected in March 2017, citing the opinions of bus companies and opposing trade unions.

But then every fatal bus accident tells a similar story.

When a Citybus double-decker mounted a pavement in Sham Shui Po in September 2017, killing 2 and injured 30, the man behind the wheel was later revealed to have been working 13-hour shifts for several days before the crash. It also emerged that near 20 per cent of the company’s drivers worked at least 12 hours a day, including 5 per cent who worked more than 13 hours.

The accident prompted Chief Secretary Matthew Cheung Kin-chung to demand the Transport Department to review the much criticised policy on working hours.

But Kwok, who attended the two consultation meetings held in last October and December, said the department told his union in early February this year – days before the even more deadly Tai Po bus crash – that it had yet to pin down a deadline for the review.

Two weeks after the repeat tragedy, when the department hastily announced the decision to reduce maximum duty hours to 12 and driving hours to 10, and at the same time including the 14-hour special shift in the guidelines, Kwok was disappointed, worrying it has given the nod to the practice.

In fact, following the announcement, the other two franchised bus operators Citybus and New Word First Bus have indicated they would consider reintroducing special-shift duties – an arrangement they scrapped in 1998.

“Every time a fatal accident occurs, people would become concerned about bus drivers’ working conditions, asking whether hours were too long, or whether the pay was inadequate,” says Kwok.

“But then, nothing changes after the dust has settled.”

On 13 March, the same day Kwok was given his new 14-hour schedule, Chief Executive Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor announced she had appointed an independent review committee to look into the operation and management of Hong Kong’s franchised bus services.

The study will conclude in nine months, but it begs the question: For how long do bus drivers like Kwok still need to endure these 14-hour journeys?